by Luc Noppen*

When discussing the problematic future of Churches throughout the Christian West, we must specify that the future of church buildings used as places of Christian worship as opposed to other religious movements is really what is problematic.

Québec. A circus school occupies the former Saint-Esprit church. It is today the most frequented church on sundays in Québec City. Photo François Bastien

It is indeed the collapse of religious practices, and therefore a drastic drop in attendance at these monuments, which mobilizes both their owners (Churches or public authorities, depending on the case) and heritage actors and activists. This then raises the issue of the survival of these churches and especially, as we shall see, the new uses that could give them another lease on life, residing in their heritage.

New Uses?

The future of churches inevitably involves the invention of new uses for these places, a matter utterly unimaginable 30 years ago. But in many cases, we must first invent a new ownership system before new occupants can move into the monuments abandoned by worshippers. Very often, in particular across America, churches are private property: they still belong to parishes, dioceses and religious congregations. Yet these organizations do not have as a vocation – in a number of districts they simply do not have the right – to metamorphose into development project promoters in the churches or on their sites. Elsewhere, even if the state or municipalities took ownership of this real estate –as is the case in France in particular – the adopted ownership system hinders the renewal of uses. Regardless of whether these buildings are already publicly owned, it is not easy, pursuant to the laws and regulations that led to their “nationalization,” to assign them a purpose other than that of worship. Public opinion – in the collective imagination where the weight of the sacred still weighs heavily – also often impedes the secularization of this heritage. If, as is commonly believed, heritage consecration involves “sacralization,” religious heritage enjoys such a status in the realm of public opinion.

The sacred landscape is metamorphosing

That said, it must be recognized that the Christian West is not as homogeneous as one might think. Disenchantment with worship is variable: in the west we are closing churches while further east, people are still fighting to reopen and restore them (but for how much longer?). In the northern hemisphere, it is the historical churches that suffer from an accelerated dechristianization; in the United States a strong spirituality characterizes the new religious traditions, in particular evangelical ones, which recruit very successfully. In Canada, but also in Brazil, many Christian churches that are closed to worship are taken over by evangelicals, Baptists, Pentecostals groups, and others. Throughout the West, sizeable Buddhist, Sikh and Muslim sanctuaries are also emerging. Established to accompany the migration of populations, these new sacred sites also attract an ever-increasing number of Westerners in search of spiritual renewal. The sacred landscape is metamorphosing, leaving many venerable historical Christian monuments behind.

La Durantaye. Saint-Gabriel church has been converted to become a community center for a village of 800 inhabitants. Still used for some religious ceremonies. Photo Jean Mercier

Who will take charge of the sites abandoned by historical Churches?

The question of ownership is being raised far and wide. Who will take charge of the sites abandoned by historical Churches? Then there is the question of uses, because we can already predict that soon it will be the most valuable and historical churches, including those falling under national legislation, which will call for attention. Boldness and innovation will be required to ensure the survival of these precious monuments, with their works of art and sacred objects. The Christian West simply has too many of these monuments to offer them for the sole purpose of the enjoyment of tourists and visitors. Moreover, we are beginning to realize that the legal protection of a building as a historical monument has its limits; this label can in no way be a substitute for its use. If it is conceivable that the heritage value of a church or its symbolic value (as a sacred place) can justify public funding in a conservation and maintenance program, it is difficult to envision the future of so many monuments that would become “useless.” In this way, our new technological and virtual world poses an increased threat to the conservation of obsolete objects. Why endure the clutter of these monuments that are so easy to reconstruct virtually for everyone to get to know and see? In today’s Quebec, a modern church is being demolished – Notre-Dame de Fatima, a true icon of the twentieth century – specifying that it will be preserved virtually (all that needs to be done is to scan and model it) in the collective memory!

Furthermore, how do we justify preserving, at great expense, monuments that more and more become detached from their initial meaning in the societies that bear them? I regularly see a fair number of students who have never set foot in a church, for whom the ecclesial attributes and characteristic features of these monuments are unknown or look bizarre. The typology of furnishings and objects intended for worship, as well as the utility/use of these objects and the meaning of Christian iconography have no resonance with these young people who have grown up outside the arcana of Christian culture, which we all shared not so long ago.

Montréal. Former Notre-Dame-du-Perpétuel-Secours has been taken over by Groupe Paradoxe, a social economy association, and converted into a theatre. Photo Saul Rosales.

To accompany the slow but certain disaffection as regards places of worship, the idea of sharing the premises has developed. The big naves could thus receive some certified and compliant uses (by whom?), to support a recovered economic value of use. But experiments so far show that this is an illusion: when the church loses its first and exclusive destination, believer disaffection accelerates. Shared use then appears as a transition, a fade out, towards complete secularization.

Sacred places, secular interpretation

The nagging question that then arises is how to build a secular interpretation of these sacred places that is anchored in the sensitivities of our age? In the West, only collective appropriation and the insertion of this heritage in our societal project will serve to mobilize energies and resources to ensure long-term survival.

A local branch of the municipal library has been relocated in a well known modern monument, the former Saint-Denys-du-Plateau church, built in 1961. Photo Luc Noppen

Such questions (and, of course, a number of others) will be raised during the 3rd Conference of the Association for Critical Heritage Studies to be held in Montreal from June 3 to 8, 2016. A number of the 800 or so participants, from 86 countries, will debate in several sessions this broader issue of “religious heritage.” Many members of Future for Religious Heritage will attend this meeting; several of them have proposed sessions or papers, of which the most important are listed below.

Session Beyond re-uses: the future of church monuments in a secular society, chaired by Lilian Grootswagers and Édith Prégent

(Monday, June 6, in historical Saint-Michel de Vaudreuil Church in Vaudreuil-Soulanges regional county, west of Montreal).

All through the Christian West, more and more churches are closed to worship, and recycling or converting to new uses has become commonplace. What has not yet been seen is a church renowned for its artistic value, a “monument” in the strict sense of the word, being totally abandoned by the group of faith, along with its religious references, fundamental for the understanding of the artistic value itself. While it is now well known that increased social and global mobility threatens our traditional views on heritage in general, interpretation and education schemes are often put in place to overcome the lack of public memory and common backgrounds on which the common recognition of heritage usually relies: everybody can learn milling at the mill, or farming at the farm, even though they have no previous knowledge or family experience of these practices. But what about the religion that bears the meaning of the most renowned religious works of art? What is the importance of the Sistine Chapel ceiling for someone with no knowledge of the Last Judgement, let alone of Michelangelo, not to mention of the so Europe-centred 16th Century?

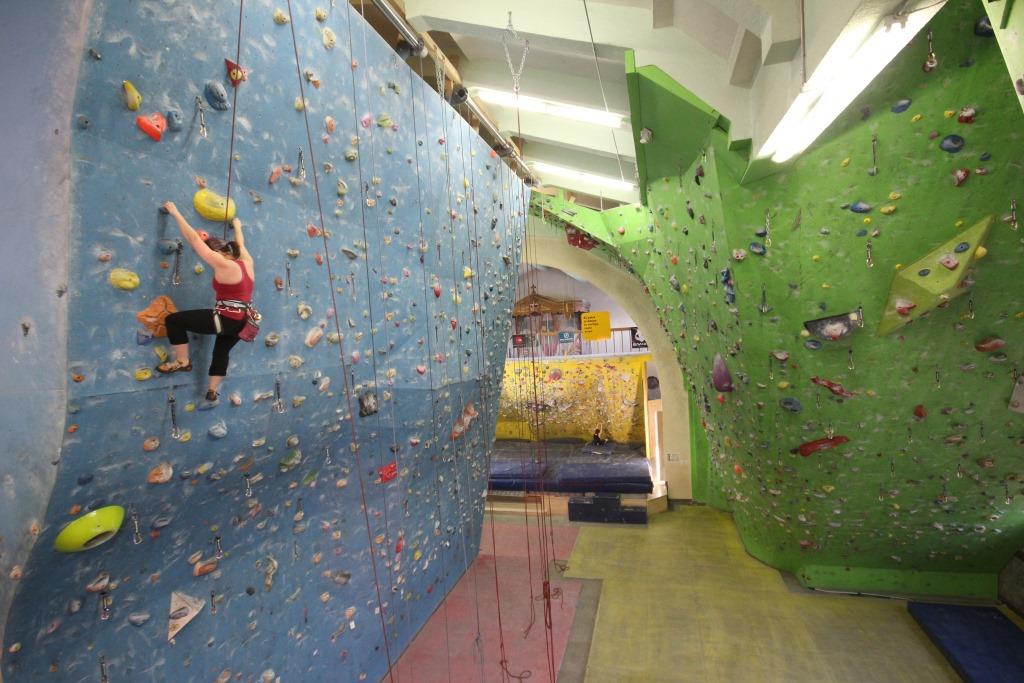

Sherbrooke. Vertige Escalade has converted the former Christ-Roi church in a sport facility. Photo Luc Noppen

While we can admit that the traditional religious practices and knowledge that produced these Gesamtkuntswerke – as one could name the “total work of art” that describes some unique monuments left by Christianity – will soon be long gone, we have to question the means and the very reasons of their survival as a heritage that fewer and fewer people would share.

This session will provide an opportunity to discuss experiments conducted throughout the Western World and bring together different viewpoints on the economy, the interpretation and the in-situ preservation of works of art, notably to grasp the legal, financial and societal implications and means of heritage-making when it puts into question the consistency of monuments previously thought to be “untouchable.”

Session Heritage and the new fate of sacred places, chaired by Chantal Turbide and Luc Noppen

(Tuesday, June 7 PM at Saint-Joseph Oratory, a famous place of pilgrimage in Montreal which houses the tomb of Saint Frère-André)

While historical churches are being abandoned all over the Christian West, more and more other places grow the opposite way: pilgrimage sites are being enlarged and enhanced, whole urban districts are being developed with churches and temples boasting diverse, and often unorthodox, religious practices. Epistemologically linked to heritage, the sacred now seems to follow a path of its own, staging itself in new settings where “religious heritage” refers mostly to common practices, however recent they may be. This new heritage-making through both spectacle and commonality, which leans heavily on the intercultural as an intangible matter, seems to leave aside the tangible side of heritage. But it has to be observed that, however intangible the practices and communities may be, all these new or renewed sacred places are conceived as and made of very tangible landscapes, buildings, and artefacts, and are set with urban planning rules, by-laws, legal status and tax systems.

If, as it has been demonstrated elsewhere, neither the religion nor any specific denomination can be seen as solutions to the safeguarding of historical churches, is there nonetheless something to be learned for redundant churches in this new fate of sacred places? How can the legal status of these pilgrimage sites and other “highways to heaven” in our secular society be compared to that of former church monuments? Can the trans-cultural way to produce the meaning of these sacred places hold any lessons for the interpretation of old churches now deprived of meaning?

Session Religion as Heritage – Heritage as Religion, chaired by Ola Wetterberg, Magdalena Hillström and Eva Löfgren

(Saturday, June 4 and Sunday, June 5. DS building, Université du Québec à Montréal)

Today one may argue that secular conservation values are increasingly invested in religious buildings and artefacts. The principle theme of this session concerns the link between the religious/pastoral values of churches and their historical/heritage values.

Exploration of the interaction of different value spheres in church maintenance relates to a number of research fields, such as museum and cultural heritage studies, including both the intertwining of religion and material culture and cases of heritage conservation practice, secularization theory (now strongly affected by the debate on the validity of the classical secularization thesis of Weber, Durkheim and Parsons), memory and identity studies, and the broad research field tied to the concept of intangible heritage, and research on the history and theory of professions within the heritage conservation field in which church renovation and restoration ideology have always played a crucial role. Most obviously the tension between pastoral and historical value poses a burning theological problem concerning the meaning and function of late modern religious practices.

* Luc Noppen is professor at Université du Québec à Montréal where he held the Canada Research Chair from 2001 to 2015; he is now Director of Partnerships for the Chair and leads a team working on a vast “churches plan” in various regions of Québec (Canada). Conducting research on the religious architectural heritage since 1972, he has written around two hundred books, reports and scientific articles on the subject. He has also organized a number of scientific meetings in this regard, including the What Future for Which Churches? international conference held in Montreal in 2005. This meeting sparked the idea of creating Future for Religious Heritage, an organization founded during the international symposium convened in Canterbury in 2010.

Follow us: