The meaning of religious heritage can go beyond that of a place of worship. The Church of Christ’s Resurrection in Kaunas, Lithuania, represents Lithuanian statehood and identity as Giedrė Jankevičiūtė, professor of art history in Vilnius, explains in the following article.

It is impossible not to draw attention to the white cube with the tall tower on the top of the hill when wandering around the city center of Kaunas, Lithuania. The building is a three-nave basilica, known as the Church of the Resurrection, and one of the important examples of local modernism.

Historians of architecture try to relate the Church of the Resurrection, which began to rise on the slope of Žaliakalnis (Green Hill) starting from 1934, to the Stadtkrone conception by the avant-garde architect Bruno Taut. Taut hoped that modernist architecture would help to mitigate national and social differences by transforming post-war European cities. Yet the search for national identity led the architects of young countries of the interwar period and their customers in another direction. So the Church of the Resurrection was above all perceived as gem in the crown of the young national state, the national monument, rather than point of reference in the urban plan of the democratic city.

Inside the Church of Christ’s Resurrection

The idea to build a monumental church that would symbolise the Resurrection of Jesus Christ and, alongside, the Lithuanian nation, and would become a sign of gratitude to the Lord, i.e. perform the function of a religious votive, was born in 1922. Among the examples that inspired the initiators of the Lithuanian project were the Vienna Votivkirche (1879) and the Basilica of Sacré-Coeur in Paris, which rose on the top of Montmartre hill rapidly urbanised in 1873–1914 and was meant to instil hope and confidence in the French people in the wake of the painful defeat in the war with Prussia. There were plans to expand and deepen the symbolism of Lithuania’s memorial sanctuary by installing a national mausoleum for highly distinguished figures of public and national importance in the church crypt.

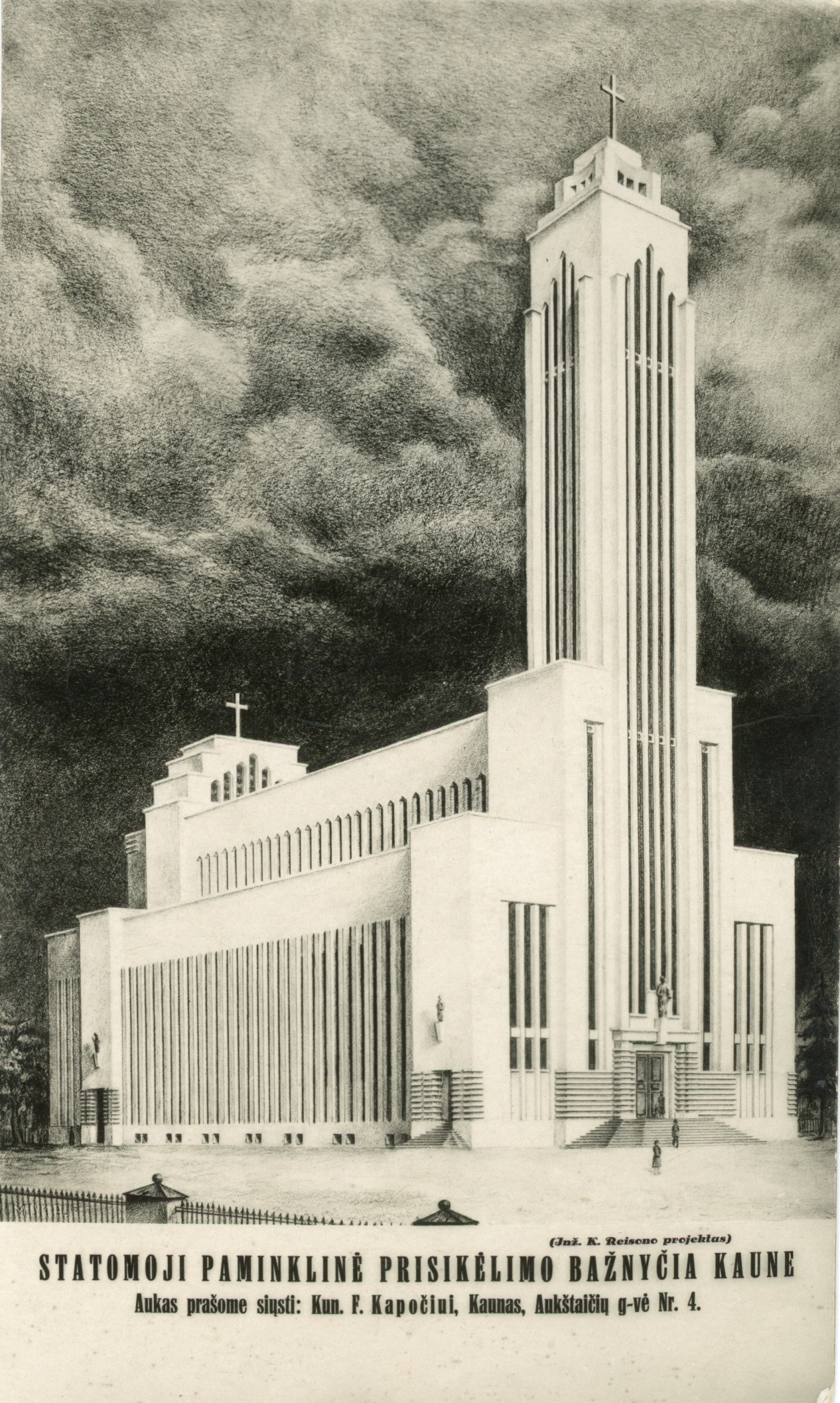

The competition for the Church of the Resurrection was announced in 1928 to mark the 10th anniversary of the state’s independence. The architects had to fulfil three basic requirements: to give the sanctuary the form of a monument, to design a space for a mausoleum, and to convey “the spirit of Lithuanian construction”. Correspondingly, the terms of the competition included the criteria for the participants’ eligibility: it was open exclusively for “Lithuanian citizens, citizens of Lithuanian origin residing in foreign countries, and foreign citizens residing in Lithuania,” i.e. those who were familiar with the aforementioned spirit or at least were capable to feel it. The project of the third-place winner Karolis Reisonas (or Kārlis Reisons in Latvian), the head of the Kaunas Urban Construction Department at that time, was chosen to be implemented. Reisonas was a Latvian (he got Lithuanian citizenship only in 1932) and an Evangelical Reformer (even if later he converted to Catholicism). These two circumstances were used as a weighty argument by the project’s opponents. Here, an analogy with the opposition against the Slovenian architect Jože Plečnik, which appeared at a similar time in Prague, unwillingly presents itself.

Reisonas gave free rein to his imagination and designed a spectacular 83-metre spiral tower of reinforced concrete, which was to be crowned with a 7-metre high statue of the Risen Christ. The stairs on the exterior of the tower had to be decorated with sculptures and marble columns with lamps, whose light would be visible from all over the city in the evening. It is obvious that the architect cast a glance at the neo-Gothic Votivkirche in Vienna, and was quite likely impressed by the spiral tower of Copenhagen’s Church of Our Saviour.

Outside the Church of Christ’s Resurrection

Politicians and the majority of church and public figures were fascinated by this fantasy. Yet several more rationally thinking representatives of the cultural circles were opposed to this utopian proposal. Reisonas redesigned the church, and on 21 April 1933, a project of a three-nave basilica of clear geometrical forms with a bell tower and a chapel on a flat roof was approved.

The foundations of Resurrection Church were laid in the summer of 1933 — a process that, according to architect Reisonas, was truly technically challenging, as it was the first attempt in the history of Lithuanian civil architecture demanding such thorough preparation. Nine hundred concrete pylons were sunk into a sand bed for the foundation, at depths of 3.5 to 6.5 metres — exhausting nearly the entire amount of funds raised thus far. The shipment of a cornerstone from the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem was equally costly.

The ceremony of laying the cornerstone of the church was planned to coincide with the First National Eucharistic Congress that took place in the summer of 1934. After construction stalled, fund-raising efforts were renewed. Every potential supporter was given the opportunity to purchase a brick for placement in the church walls. The campaign was a success. In the summer of 1936 alone, nearly 150,000 litas were raised, while more affluent donors extended zero-interest loans for the construction.

In 1936, the walls were built, in 1938, the roof was treated with concrete, and a bell tower began to rise. Even in 1937, however, radio broadcasts were still encouraging listeners to visit the donation booth at the construction site. By 4 January 1940, construction costs had reached 878,470 litas: 590,000 litas funded by public donations and the remainder from the government.

According to documents, in 1939, two staircases leading to the roof were built, oak window frames adapted for stained glasses were installed (the artists Stasys Ušinskas and Liudas Truikys were commissioned to create stained glass windows, and negotiations for their production were started with Franz Mayer’s workshop in Munich), wood for the doors was prepared, and interior plastering began. Plasterwork on the church exterior was not finished before the Soviet occupation.

From 1940, the temple unexpectedly turned into a symbol of the loss of statehood. The Soviets nationalised the unfinished building in 1941. A year later, the Nazis converted it into a paper storage. In 1952, the church was adapted for the needs of a Soviet military complex and produced also radio and, later, TV sets for civil needs. In the process of creating the manufacturing facilities, the interior of the church was partitioned with concrete slabs between the floors, and the redundant chapel on the terrace was pulled down. Equipment was installed in the newly-formed production departments, and auxiliary premises, a design department and other buildings were constructed in the churchyard. As the first signs of the imminent fall of the Soviet regime appeared in 1988, demands were voiced to move the factory out of the building and to return the church to worshippers.

The massive redbrick structure dominated the Kaunas cityscape for fifty years as a reminder of the unfinished construction of a national symbol and the aim of the restoration of independence; it was not until the early 21st century that the church was plastered white, after having been returned to the Catholic Church. The reconstruction was finally completed in 2004 according to the project of the renowned Kaunas-based architect Antanas Algimantas Sprindys. A parish hall was completed on the southwestern side of the church in 2009. A chapel dedicated to the Our Lady of Šiluva was installed on the flat roof and a columbarium was established in the church basement to honour the remains of those who had served the Church, nation and state.

By Giedrė Jankevičiūtė

Follow us: