In September 2022, the European Commission published the report “Strengthening cultural heritage resilience for climate change: Where the Green Deal meets cultural heritage”. This report provides, for the first time at the European level, an overview of the extent to which climate change and cultural heritage policies converge or complement each other in the different European countries, identifying the main weaknesses and gaps for cultural heritage to become more resilient to climate change. It also gathers 83 excellent examples of the ways in which cultural heritage can contribute to the European Green Deal and to providing sustainable solutions to tackle climate change.

The report has been prepared by the Open Method of Coordination (OMC) expert group, which is a special non-binding legislative procedure in which each country participating in the report appoints a national expert to work in coordination with other experts and formulate recommendations for the EU Commission.

The OMC expert group included experts nominated by 28 countries (25 Member States and 3 associate countries): Austria, Belgium, Croatia, Cyprus, Czechia, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden and Switzerland.

10 key recommendations

The main purpose of the report was to provide recommendations to the European Commission to strengthen cultural heritage resilience. These recommendations have been based on the analysis and discussions of the OMC group in their nine meetings held in 2021-2022. The 10 recommendations for the EU Commission are:

1. To emphasise the importance of cultural heritage and propose new actions

2. To ensure structured cooperation between EU directorates-general for climate change and cultural heritage

3. To develop and regularly update a European climate change cultural heritage risk assessment map by 2025

4. To review the economic costs of climate change adaptation for cultural heritage

5. To establish a common EU platform for exchange, discussion, and knowledge sharing about the impact of climate change on heritage.

6. To integrate culture and cultural heritage issues into environmental sustainability and climate policy-making at all levels (local, regional, national, European, international).

7. To build capacity and multidisciplinary expertise on cultural heritage and climate change through education, training and upskilling

8. To invest more in research at the national level in order to share knowledge and cooperate in analysing data, creating strategies and developing tools at the EU level.

9. To implement monetary and fiscal policies at the national, regional and local levels to incentivise the safeguarding of cultural heritage.

10. To increase cooperation in all Member States between those responsible for climate change and those responsible for cultural heritage.

Key findings of the report: weakness of policies and the threat of extreme climatic events

The first task of the OMC group was to compile data about the state of play of cultural heritage and climate change policies in Europe. A questionnaire was sent to the participating countries in the report.

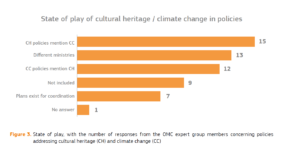

From the 26 countries that answered the question on the state of play, 9 do not have any legal framework connecting cultural heritage (CH) and climate change (CC), although 7 have plans to develop one. It is also of concern that 13 countries have different institutions and/or ministries dealing with climate change and cultural heritage separately. The questionnaire also showed that 15 countries include some mention of climate change in their cultural heritage policies and 12 include some mention of cultural heritage in their climate change policies.

In the light of these results the report states: “the information gathered is shocking: cultural heritage is under attack from climate change at an unprecedented speed and scale. Yet EU Member States do not have proper policies and action plans in place to mitigate these attacks, nor does the EU.”

Source: Strengthening cultural heritage resilience for climate change (page 15).

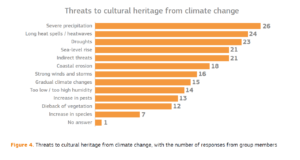

The OMC group also identified the biggest climate threats to cultural heritage. Severe precipitation, heatwaves, droughts and sea-level rise are at the top of the list. These are the most visible effects of climate change and also the phenomena that most directly impacts cultural heritage.

The report also stresses the need for attention to gradual climate change: “Gradual climate change – a continuous increase in temperature, fluctuations in temperature and humidity, and fluctuations in freeze–thaw cycles – should not be neglected (i.e. the focus should not be on extreme events only), as it causes increased degradation and stress in materials, leading to a greater need for restoration and conservation.”

Source: Strengthening cultural heritage resilience for climate change (page 17).

83 best practices around Europe

The report concludes with 83 excellent examples of innovation, resilience and measures taken to respond to climate change challenges. The OMC expert group hopes that these good practices will become a source of inspiration: “This large number of case studies and countries clearly testifies to the commitment of the countries to develop pioneering projects and to promote knowledge of the issue of cultural heritage resilience in the face of climate change”.

The following are some of the examples involving religious heritage:

Aerial view of Ballinskelligs Priory, Ballinskelligs, Co. Kerry, Ireland. © 2020, Photographic Archive, National Monuments Service, Government of Ireland

Ballinskelligs Priory (Ireland)

The 12th-century abbey on the shore of the Ballinskellings Bay was the first national monument site in Ireland where a climate change risk assessment was performed. This World Heritage Site includes the ruins of two churches, a cloister garth, a large hall and a graveyard that is still used by the local community. Storm damage and coastal erosion are now threatening its future. A significant proportion of this historic site has already been lost to coastal erosion despite the defense wall built in the 1950’s and the repair works carried out in the last 10 years. The Irish Office of Public Works began monitoring the rate of coastal erosion at the site through an annual drone scan. This will also help identify and plan the necessary repair works in the upcoming years.

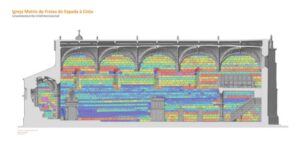

Freixo de Espada à Cinta Church: threedimensional mapping. Height of rows. ©DRCN/SIAP/Orlando Sousa ©FAUP/CEAU/Hugo Pires

Artificial intelligence system for cultural heritage (Portugal)

This research project consists in the development of an artificial intelligence (AI) prototype for monitoring minor changes such as micro and macro movements of the ground on which buildings stand, changes in the position of buildings and the detection of biological infestation in heritage buildings. The prototype is being developed by collecting satellite and alphanumerical data and performing a 3D scanning of three churches in northern Portugal: Freixo de Espada à Cinta Church, Vila Nova de Foz Côa Church and Torre de Moncorvo Church. This will allow heritage professionals and authorities to detect minor changes in heritage buildings in a non-intrusive way, avoiding high-impact interventions, as well as unnecessary and costly actions. It will be particularly relevant in sites such as coastal or underwater heritage.

View of the church town of Lövånger. Source: lovangergarden.

Church villages (Sweden)

Church villages are a unique type of medieval village found only in Sweden and Finland. These villages usually consist of a group of small cottages built around a central church. Their purpose was to house worshippers from the surrounding countryside who, due to the distance, could not return home on the same day during religious festivals and on Sundays. Most of the buildings in these church villages now belong to private owners. In an effort to educate owners on preventive maintenance of these historic buildings, the County Administrative Board of Norrbotten County in northern Sweden has produced a brochure with a checklist on the different types of damage related to changing weather conditions (drainage, frost and growth of moss, mould and fungus, etc.) and how owners can monitor the changes and react to this damage. The brochure is called “The church towns of the age of climate effects” (Kyrkstäderna i klimateffekternas tid) and is available here.

Follow us: