The remodelling of a historic religious space for contemporary usage as a place of worship, its original purpose, can mean conflicting interests of users and conservationists. Changes of liturgical requirements imply alterations of historic religious interiors. Art historians try to preserve the historic interior, the faithful wish to celebrate mass according to a prescribed liturgy. The new liturgical space in Pannonhalma Basilica, Hungary, is a minimalist intervention respecting both heritage values and contemporary users.

Confrontation by the historical and use values of the built heritage was always a controversial question among conservation professionals since the first well-known essay of Alois Riegl in 1903. Appropriateness of the inner space for the certain liturgy and common expectations of the faithful mean the use value of the sacral buildings. Changes of the needs can cause the demand for the alteration of the interior.

Sacral spaces with the adequate arrangement of the liturgical furnishing have to serve the liturgy and contemplation. The Roman Catholic liturgy did not change considerably for the centuries, but the necessity for the theological revival became acute for the 20th century. The liturgical reform of the Second Vatican Council (1962–1965) realized this intention. Vatican II Constitution and Instruction urged the communal service of God and full attention to the Word. The new liturgical requirements were easy to adopt into new churches, but it often meant hard challenges for the listed monuments. The reform endorsed the use of the new, contemporary liturgical objects with high artistic value and obviously disavowed from the copy of the old styles. According to the instructions, almost all of historic churches in Hungary were rearranged from the mid-1960s. After the purist-approach monument preservation interventions of the 19th century, these liturgical space rearrangements were the first greater consequence alterations in the 20th century, which affected numerous churches. Understanding and reconsideration of the liturgical spaces got into the focus point of the international liturgical conferences and meetings from the 1990s. Plans for reorganizations followed a completely minimalist style from these times, and the visual-aesthetic claims of the users often got the better of the monument preservation principles.

A spectacular example of the revival of a valuable historic church is the Saint Martin basilica in Pannonhalma, which is the first monastic church in Hungary – thus it is considered as one of the most valuable sacral buildings in the country. Pannonhalma was populous from the early times, but the quick development of the settlement started with the settling of the Benedictine Order in 996 (at the early time when Hungary became a Christian Kingdom). The abbot invited Cistercian masters for the construction of the basilica, which was rebuilt several times during the centuries, but main parts of the church were built between 1217 and 1225. Meaningful remodelling happened in the 1870s according to the plans of Ferenc Stornó, a purist-approach monument preservation specialist, who carried out significant decompositions and created an integrated Gothic style interior. Restoration of the Benedictine Abbey of Pannonhalma – Unesco World Heritage Site since 1996 – became timely to the millennium of its foundation, so the main parts were carefully restored, and parallel with this, some new service buildings were constructed all around the abbey. These significant contemporary developments evolved an individual, special atmosphere together with the highly appreciated historic heritage.

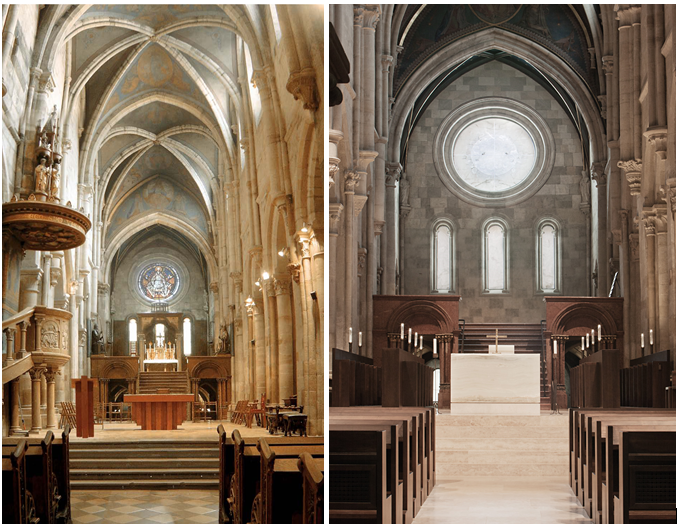

Renewal of the basilica interior left for the 2000s. The Basilica Workshop was established in 2003, which was responsible for the theological and professional preliminary works. Finally, the monastic order entrusted the British designer, John Pawson – co-operating with the Hungarian 3h architecture partner office – with the interior design. The aim of the renewal was double: on the one hand evolving enough well organized seats simultaneously for the monks and the laical faithful, on the other hand simplifying the interior from the confusingly numerous, mixed, historical layers to reach a minimalist and calm contemporary sacral space. The architects intended to remove the unused 19th century liturgical objects (neo-gothic pulpit and ciborium), thus the planum would become better utilized and the interior would be more unified. However, the removing of these historic furnishing was a truly divisive question among the Hungarian professionals, because the art historians and the architects represented strongly different point of views. By reason of the intense disputations, the renewal passed off in two phases: the main part of the works was finished in 2012, while the final intervention in the apse, to make the whole composition accomplished, was done in 2015. Ultimately the scheme of the sacral space became clear. The liturgical objects are organized on a sacral axis from the west end of the church right up to the eastern spatial wall, and all of them were designed from the same noble material, the onyx. The starting point of the sacral space is the mystery of the light, when it shines through the thick onyx sheet in the symbolic rose window above the western gate, following that the baptismal font comes under the tower, then the altar and the ambo can be found on the planum – a few steps higher than the pews –, and finally the window of the eastern wall closes the line of the elements. The most concentrated point of the interior is the apse, where the horizontal axis of the liturgical objects and the vertical axis of the space (the so-called axis mundi, which is the connection between Heaven and Earth) cross each other. This accentuated point is emphasized with an onyx tile on the top layer – above the crypt and under the stellar vault. The space of the apse is completely empty, as the transubstantiation happens here during the liturgy.

The renewal of this basilica cannot be considered as a restoration. A new entity was born, which reflects on the historic parts of the church, and at the same time uses contemporary materials and forms. Revival of the historic churches often goes hand in hand with hard conflicts between the monument preservation principles, contemporary liturgical requirements and the minimalist aesthetic claim of our days. This kind of confrontation can be caught out continuously from the liturgical reform of the Vatican II, so we have to reconsider its constitutions and instructions again, to practice a more careful and reflective sacral monument preservation in the future.

Author: Erzsébet Urbán, architect and post-PhD student

Follow us: