FRH invites you to walk the world-famous Camino de Santiago alongside our member, Maaike de Jong. Over the coming weeks, Maaike will share weekly reflections from the trail, offering a unique insight at the rich heritage she encounters—not only in the form of historic monuments and sacred sites, but also through the living traditions, stories, and people that keep the Camino’s spirit alive.

Follow her footsteps and reflections each week on our Instagram, Facebook and LinkedIn accounts.

First week| The story of Santo Domingo de la Calzada

Dear FRH community,

My name is Maaike de Jong. I work in the field of sustainability and cultural heritage, and at the moment I am on the Camino Francés, the historic pilgrimage route that leads to Santiago de Compostela together with my husband Alexander. Over the coming weeks, I will share images and reflections from the road, with a focus on SDG 11.4: safeguarding cultural and natural heritage.

Walking through northern Spain, heritage is not just something you visit in a museum, it surrounds you at every step. Two stories in particular have struck me deeply:

- The bridge builder: Santo Domingo de la Calzada (1019–1109)

Known as “the saint of the road,” Domingo dedicated his life to making the Camino safer for pilgrims. He built bridges over the rivers and laid causeways across the marshes, often with his own hands. His work is a reminder that infrastructure itself can be heritage, form of care and solidarity preserved in stone. Even today, pilgrims cross bridges that bear witness to his vision of hospitality. - The miracle of the chickens. In the cathedral of Santo Domingo de la Calzada, a live rooster and hen are still kept in memory of a medieval miracle. According to the story, a young pilgrim was falsely accused and hanged, but miraculously survived. His parents appealed to the local judge, who mocked them by saying their son was as alive as the roasted chickens on his plate. At that moment, the chickens jumped up and crowed. Since then, the presence of living birds in the church has become a tangible sign of faith, justice, and wonder, heritage that is both symbolic and very much alive.

These encounters show how heritage on the Camino is layered: it is physical (bridges, roads, churches), narrative (the legends and stories), and living (traditions that continue in practice today). For me, it highlights the importance of walking as a way of experiencing heritage not just as a monument, but as a living, shared reality.

I look forward to sharing more of these discoveries with you in the coming weeks, and to reflecting on how pilgrimage routes like the Camino can inspire our broader work of sustaining religious heritage.

Warm greetings,

Maaike de Jong

From left to right: Mosaic of the miracle of the chickens. Chicken coop on a portico inside the cathedral of Santo Domingo de la Calzada. Façade of the cathedral of Santo Domingo de la Calzada at night.

Second week | Astorga: Crossroads of Rome, Faith, and Pilgrimage

My second week on the Camino Francés has brought me to Astorga, a city where the layers of history are unusually visible. First established as the Roman camp Asturica Augusta, Astorga lay at the intersection of ancient roads that carried soldiers, traders, and eventually pilgrims. Even today, the Roman grid and remains beneath the streets remind us that pilgrimage in Spain is never only medieval but always built upon older routes of empire and exchange.

- The cathedral of Santa María dominates the skyline, I could see it from far away. Construction began in the 15th century, but the building is a tapestry of styles: Gothic arches, Renaissance portals, and exuberant Baroque façades. To stand before it is to see faith translated into stone, while also witnessing how religious architecture along the Camino absorbed new influences over time.

- Beside it rises Gaudí’s Palacio Episcopal, a striking neo-Gothic experiment commissioned after a fire destroyed the earlier episcopal residence. Though Gaudí abandoned the project in frustration, the palace today houses the Museo de los Caminos, a fitting reminder that the Camino’s heritage is as much about reinvention as continuity.

Astorga also belongs to the Maragatería region, long known for its itinerant muleteers who connected trade across Spain. Their memory lingers in the cocido maragato, a robust stew served in reverse order, reminding pilgrims that heritage is not only monumental but also culinary and lived.

Leaving the city in the hot afternoon sun, I felt again the familiar rhythm of the Camino: moving from grandeur and history back into the quiet simplicity of the road. This oscillation between magnificence and humility, past and present, is perhaps what gives the Camino its enduring power. In Astorga, one feels that pilgrimage is not just a journey to Santiago, but a pause at the crossroads where faith, architecture, and cultural memory converge.

From left to right: Statue of St James. The interior of the Cathedral of Santa María. Astorga’s streets.

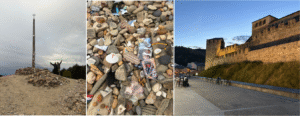

Third week | Camino Francés, Heritage along the way

The journey continues smoothly, and we walked one of the most beautiful stretches so far: from the Cruz de Ferro down through the hills to Ponferrada and further on to Villafranca del Bierzo, right in the heart of the El Bierzo wine region. The landscape itself breathes heritage: centuries-old vineyards, villages shaped by pilgrimage, and the enduring rhythm of the Camino.

At the Cruz de Ferro, high in the mountains, I too placed a stone, a small gesture in a centuries-old tradition. For me, as a modern pilgrim, it felt unexpectedly powerful: laying down that stone was more than just a ritual. It became a moment of silence, reflection, and a sense of connection with generations of pilgrims who had walked before me.

In Ponferrada, the impressive Templar castle rises over the city. Since the Middle Ages, the Knights Templar guarded the safety of pilgrims facing the difficult and sometimes dangerous stages through the mountains. Walking along its walls, I could feel how their presence still shapes the pilgrimage experience today, a symbol of protection, but also of the challenges that are part of the journey.

Further along, in Villafranca del Bierzo, often called the “little Santiago”, I was struck by its unique tradition: pilgrims who, through illness or exhaustion, could not complete the road to Santiago were still granted a full indulgence here. This medieval practice shows that heritage is not only built of stone but also embodies values of care and compassion that remain meaningful across centuries.

For me, as a modern pilgrim, this layering is what resonates most: heritage as architecture, ritual, story, and human value. It shows how religious heritage along the Camino is more than history, it is living heritage, still offering strength, comfort, and inspiration today for many along the Way.

From left to right: Cruz de Ferro (Iron Cross). Stones left by pilgrims at the base of Cruz de Ferro. Templar Castle in Ponferrada.

Fourth week | A living dialogue between the past and present

After days of steady walking through the mountains, the climb to O Cebreiro felt like crossing a threshold between worlds. The mist thickened as the road wound upward, revealing stone houses with thatched roofs, the pallozas, that recall a Celtic past. This mountain village, perched at 1,300 meters, marks the symbolic gateway into Galicia, a region long associated with ancient sanctuaries and enduring pilgrimage traditions.

At its heart stands the church of Santa María la Real, one of the oldest on the entire Camino Francés. Built in pre-Romanesque style around the 9th century, it is famous for the Eucharistic Miracle of O Cebreiro. According to legend, during a storm in the 14th century, a local peasant attended Mass despite the priest’s disbelief in the Real Presence. When the priest mocked his devotion, the bread and wine miraculously turned into flesh and blood, a story later cherished by pilgrims and even by the Catholic Monarchs, who ordered a reliquary for the miracle. The church still exudes a quiet sense of wonder, connecting centuries of faith, doubt, and renewal.

A few days’ walk further west lies Samos, home to one of Spain’s oldest and largest monasteries. The Monasterio de San Xulián de Samos was founded, according to tradition, in the 6th century and later embraced the Benedictine Rule. Over the centuries it became a beacon of learning, manuscript preservation, and hospitality. Even after fires, suppressions, and restorations, the monastery continues to shelter pilgrims, fulfilling the ancient Benedictine teaching “Let all guests be received as Christ.” Its grand cloisters, echoing corridors, and quiet church form a living archive of European monastic culture.

Walking between these two sacred sites, I was struck by how the Camino weaves together layers of tangible and intangible heritage, architecture, ritual, and human encounter, into a living dialogue between past and present.

From left to right: Church of Santa María de O Cebreiro. Maaike resting along the camino. Monastery of San Xulián de Samos.

Fifth week | Reborn from the Water: Portomarín and the Living Memory of the Camino

After walking more than five hundred kilometres along the Camino de Santiago, each step now carries not only a bit of fatigue but also layers of history. Today’s stage brought us to Portomarín, a town that quite literally rose again from the waters, a striking example of how faith, memory, and community can reshape the past to secure the future.

We left before sunrise, the air veiled in mist, the sky a soft grey-blue curtain pierced by early light. Along the path we shared that familiar pilgrim rhythm of overtaking and being overtaken: a Scottish mother and her teenage son with headphones, a lady in a pink tennis outfit striding ahead, and countless others tracing their own versions of devotion, challenge, or curiosity.

The hills of Galicia unfolded around us in gentle motion: oaks and ferns, the scent of eucalyptus, and the shimmer of light that makes even ordinary landscapes feel sacred. By mid-morning the river valley opened, and far below lay the Miño, deep and calm, holding an entire town beneath its surface.

When the Belesar reservoir was built in the 1960s, the original Portomarín was submerged. Yet its people refused to let their history vanish. Stone by stone, they dismantled the key buildings and rebuilt them on higher ground, among them the fortress church of San Xoán, also known as San Nicolás, originally constructed by the Knights of St John. The church still bears the marks of its dual purpose: both sanctuary and stronghold. Its towers and arrow slits speak of defence, while its portal carvings express devotion.

Walking into the new Portomarín, one feels the echo of the old town below, a memory literally embedded in the rebuilt stones. On certain days, when the water level drops, parts of the submerged streets and arches reappear, reminding locals and pilgrims alike that faith and heritage are never fixed. They shift, adapt, and resurface in new forms.

For those of us walking to Santiago, this story resonates deeply. Like Portomarín, the Camino itself endures through transformation, an ancient route that continues to find meaning in modern lives, bridging belief, history, and the shared experience of movement.

I have now walked over five hundred kilometres, with just under a hundred to go. By next week I hope to reach Santiago de Compostela, where I will write again from the place that has called pilgrims for over a thousand years.

From left to right: Maaike and her husband in their sixth week of walking the Camino. The Belesar reservoir, which submerged the old village of Portomarín. The fortified church of San Xoán in what is now Portomarín.

Arrival in Santiago | Walking as a Way of Caring for Living Heritage

What a journey it has been.

After walking more than six hundred kilometres, I arrived in Santiago de Compostela, following paths that millions have walked before me. What began as a leap into the unknown became a journey of encounters, reflection and quiet transformation.

Camino Francés and Routes of Northern Spain, is not just a historic route but living heritage. Each cathedral, bridge, monastery and village along the way tells a story of care, hospitality and human resilience. Walking it made me realise that heritage stays alive when people keep engaging with it, by moving through these landscapes, meeting others and renewing their meaning.

After arriving, I visited the magnificent cathedral and the tomb of Saint James. I also explored the Cathedral Museum and stood before the breathtaking Portico da Gloria, an encounter with stone that seemed to sing. This year alone, more than five hundred thousand pilgrims have arrived in Santiago, each with their own story and purpose. The city was filled with happy pilgrims, tired, grateful and radiant. It felt like a living celebration of centuries of faith, art and hospitality.

In many ways this reflects what Future for Religious Heritage stands for. The Camino unites people across generations and borders, promotes awareness of sacred places and traditions, and protects both tangible and intangible expressions of faith. It is a reminder that heritage thrives through use and connection, not through preservation alone.

For me, this walk also became a practice in sustainable leadership: slowing down, listening, trusting the path and rediscovering simplicity. It showed me that real change, like pilgrimage, requires patience, humility and care.

Arriving in Santiago did not feel like finishing; it felt like beginning again.

The road does not end at the cathedral, it continues in every step we take to keep heritage alive.

Warm greetings,

Maaike.

From left to right: Arrival in Santiago. Interior of the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela. UNESCO World Heritage Site stone.

Follow us: