Hiding in the mountains between Barmouth and Bontddu is a church of extraordinary individuality and importance.

St Philip’s, Caerdeon has been described as rustic Mediterranean, Alpine, of French Basque influence or like an Italian farm building. In 1863, The Ecclesiologist wasn’t complimentary about it, describing it as “something between a large lodge gate and a lady’s rustic dairy”.

Indeed, neither was The Ecclesiologist very complimentary about The Revd. John Louis Petit (1801-68) – the architect of St Philip’s. In 1863, that eminent publication labelled Petit “a clever amateur”. The Ecclesiologist’s disdain for Petit presumably stemmed from his openness to architectural ideas from a range of sources, collected in his book ‘Remarks on Church Architecture’ (1841), which put him at odds with advocates of Gothic Revival principles.

Whilst not a household name like his contemporary John Ruskin, Petit was one of the leading architectural writers of his age and was one of the few who resisted the ‘copy Gothic’ that was so fashionable in the 19th century. From the 1840s, he was a pioneer in arguing for the preservation of ancient churches – a time when destructive restoration was at its peak and later proposed original, modern designs for church buildings.

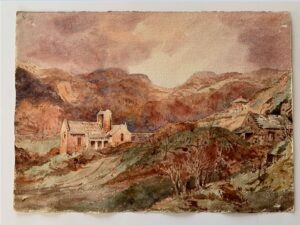

Petit was also an accomplished topographical watercolourist. His work remained hidden in the attic of a descendant for 150 years after his death. In the 1990s, the entire hoard was sold at auction. It is widely dispersed in private collections, but happily, The National Library of Wales holds the largest public collection of Petit’s artwork.

Petit painted St Philip’s throughout its construction, so we have an invaluable record of the building process. Petit’s artistic talents certainly contributed to the great success of St Philip’s: despite its continental influences, it is in harmony with its North Wales landscape; Petit achieved this through the use of local materials and building traditions. Even The Ecclesiologist had to admit that it has “picturesque appropriateness”.

The rusty, rubble-slate construction includes a lean-to loggia with stone benches and round-headed windows, and a unique bellcote-cum-chimney, which holds four bells that are rung by a large wheel in a shelter on the north side of the church.

Inside, St Philip’s is simple. The walls are white-washed and bare. The plain pews are contemporary with the construction. Decoration is saved for the sanctuary, where the mosaics and marbles give a Byzantine feel. The east window, a Crucifixion by Kempe, was inserted in 1892.

Inside, St Philip’s is simple. The walls are white-washed and bare. The plain pews are contemporary with the construction. Decoration is saved for the sanctuary, where the mosaics and marbles give a Byzantine feel. The east window, a Crucifixion by Kempe, was inserted in 1892.

St Philip’s is Petit’s only surviving building. It is utterly unique. In 2018 – four years after it closed for worship, and while its future hung in the balance – Cadw, the Welsh Government’s historic environment service, reassessed the church and upgraded its status to Grade I. The reasoning included that St Philip’s has “special architectural interest as a highly unusual and distinctive church for its period, boldly original in its style and relationship with its landscape… It gives clear expression to [the architect’s] views, which provided a counterweight to the prevailing orthodoxies of the Gothic Revival”.

“Visitors enter at their own risk”

Taped to the south door, this was the notice that welcomed people to St Philip’s. And visitors have good reason to be cautious. Chunks of plaster are dropping from the ceiling; the ancient electrics are dangerous.

The church was built on a natural promontory with the land falling away dramatically to the north, south, and west. It’s likely that the site was infilled to create a level base for the building. As a result, the church is moving – and cracking.

The complicated drainage system exacerbates this. The cracking has allowed water to soak into the building. This in turn is causing the decay and localised collapse of the lath and plaster ceiling.

Because of the clogged and collapsing drains, the walls are crumbling at a low level. The roofs, unmaintained for many years, are thick with vegetation… including some well-established trees.

In the first phase of repair, following careful assessment, we decided that all roof slopes had to be stripped and re-covered. This was the first time in its 156 years that the church had been re-roofed.

All roof slopes were stripped, the timbers repaired and where needed, replaced, and the lead flashings renewed. We had anticipated a high yield of salvage in the existing roof slates, however, when on-site, we found that many of the slates had large ferrous inclusions, which created a weakness and meant that a higher-than-budgeted proportion of new slates had to be introduced.

Rainwater goods at St Philip’s were labyrinthine. Swan-necks galore. These, coupled with years without maintenance, resulted in a lot of damage. We rationalised the rainwater goods to make the disposal system work more efficiently and effectively.

The joints of the rubble-slate walls had at one time been buttered over with a thick cementitious mortar. This was causing localised decay of the stonework and significant dampness internally. Whilst the scaffold was in place, it was prudent to rake out the cement mortar and repoint in lime mortar.

St Philip’s is now watertight. We need to undertake a drainage survey and plan repairs and improvements to this. We need to monitor the cracking. We need to overhaul the ancient electrical installation. We need to repair the glazing. We need to repair the lath and plaster ceiling. We need to patch re-plaster the walls… and redecorate. We need to raise a considerable amount to fund this work.

This is just the beginning.

Rachel Morley, Director of Friends of Friendless Churches, London, UK 2021

Photos by Andy Marshall

Follow us: