This interview is part of a series of interviews with European craftspeople conducted in collaboration between FRH, the European network for Religious Heritage, and Mad’in Europe, the network of European fine and traditional crafts and Cultural Heritage restoration professions.

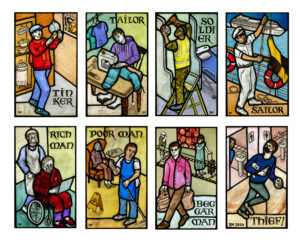

Stained glass by Rachel Mulligan inspired by the nursery rhyme “Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Sailor”. © Russell Sach.

Rachel Mulligan is a stained-glass artist based in the United Kingdom. Her work, mostly local in scope, includes both commissions for private individuals and exhibitions in museums. Currently, she is working on the design of a church window for the All Saints’ Church in Benhilton. Read on to learn more about her work, the challenges she faces as a professional and her views on how to support professionals in her sector.

1. Please introduce yourself (profession, area of expertise and years of experience).

I am Rachel Mulligan. I have been a stained glass artist for about 30 years. I design and make new windows and exhibition pieces as well, but most of my work is commissioned. I am the Vice Chair of the British Society of Master Glass Painters at the moment. As a professional group, we are working to promote stained glass and keep it alive for everyone.

2. What clients/markets do you work with (are they local, national or international)? Which are the required skills and certifications that your customers request?

If I am working to commission, people usually find me through the website or Instagram or word to mouth. I have got a lot of work locally and some nationally. At the moment I am doing a window in Shropshire, and I have also got one to do in New York, which is my first kind of international commission. So that´s quite exciting. I have also got a church window that I’m working on at the moment, at the All Saints’ Church in Benhilton, and they found me because someone recommended me for that to be put forward. So people find me through various ways.

I have also done exhibition work. I did a piece about the pandemic inspired by the nursery rhyme Tinker Taylor Soldier Sailor. So I have done a series about that and it has been exhibited at the Stained Glass Museum in Ely and the British Glass Bienniale in Stanbridge.

About the certifications, I haven’t been asked for any certifications in my previous works. I am an accredited associate of the British Society of Master Glass Painters, but no one has ever actually asked to see that. It’s more based on portfolio and experience. People can see my windows in various places and presumably word of mouth as well.

3. Please briefly explain how your profession is related to religious heritage and/or cultural heritage.

Well, each commission is different, so you start with the architecture of the building, and it needs to relate to that, the window and anything else that’s there. For example, in the church where I’m working, there’s a lot of post-war glass because the place was bombed in the war. The windows are by John Hayward and some other fairly well-known artists. So you have to take into account what else is around.

In this case, it was a legacy that someone had left some money for, so I have been working also with the son of the family, reading the brief that was left. I have also worked with the churchwardens, I’ve been to some services and met the congregation. And after all that I have done a design. I have taken it to the church to show them there, etc. It´s an ongoing process, really.

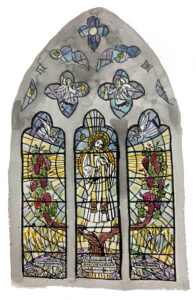

I started a year ago with this window, which is a three-light window with tracery at the top, and it has just got the DAC approval, that’s the Diocesan Advisory Committee, which is present at every diocese in the UK and has the role of advising on the maintenance and restoration of the church building. This is the third window they have looked at for this particular building. And it’s been turned down before, so I’m the third artist, and it’s got the approval. That’s a good step. Then the next step is to get a faculty, which is like the planning permission for the church. I’m hoping I can do it without any distractions in about four or five months.

Watercolour sketch of window for All Saints’ Church, Benhilton, November 2022. © Rachel Mulligan.

4. Please describe the main steps of your usual working process and the materials that you use most.

I would say that up to a third of the whole time is taken up with the design and the cartoon, getting it right on paper before going into the glass. Because if it isn’t right there, it’s not going to be right down the line. And you invest a lot of time in doing it.

I work initially with charcoal on paper and then foam it up into pencil. At this stage there’s water, colour, studies and other things involved. The main material I use for the actual window is called “mouth blown glass”, which comes in sheets. It’s very expensive and very difficult to get, especially now that we’ve lost our last supplier in England. I have some stock from there as well as from Lamberts in Germany who are the main producers of it together with France. And of course, it’s all much more expensive since the energy crisis and Brexit and all that. It has doubled in price in the last three years.

Once I’ve got the mouth blown glass, I can pick out different tones of colour. I use a very traditional way of painting, which is with powder. It starts off as a powder, and you mix it with various things: water, vinegar or oil, and then you can do that as a line work. Then you might fire it in between and add tone. It’s all very fluid and you can change it. So there’s a lot of painting going on again and looking at it on the easel.

When it’s all fired and I’m happy with it, I hand it to my studio assistant who does the leading. Not because I don’t like leading, I do really enjoy it, but it’s just a part of the process that I can get someone else to do, whereas the painting I can’t really. Well, you cement it so it’s watertight and put some ties on so it can be held in place in the window. And then I use another firm to fit the windows, who are specialists at stonework and glazing.

5. Do you regularly cooperate with craft professionals from other fields?

Well, not regularly. Collaborations tends to be within the stained glass world. So as I say, I will use someone to fit my windows. It would be quite interesting though to do a project where you’re collaborating with, I don’t know, textile artists or something and do things together. But I haven’t done that.

6. Please mention any innovation that helped improve your work (technological, digital, material related, legal…) and explain the impact they had on your profession.

I have a really fast kiln that can fire glass in under an hour, the whole cycle, cook and cool. I use the engraving technique for flash glass. This has a thin layer of colour on a clear surface, and I have developed a way to take that away. And then there’s a mixing flux, which I add on top, which sort of seals it.

So these are things that I use in my own work that I have sort of developed over a few years. And I’ve managed to package them up and get something that I’m really proud of being able to share with people, something that they can then go away with.

7. How did you learn the profession?

I do a lot of learning from that heritage. I go and sketch in churches when I can and try to learn from what’s there. Obviously, the subject matter is very different from the subject matter I use when I’m doing a commission for a house, for example. And I will always sort of lean into whoever is more experienced and has more knowledge than I do to sort of find out what I need to know for that.

8. Do you pass on your knowledge to young people?

I have developed a one-day workshop for students who haven’t done any glass. Some might not have done any art since they left school. This workshop is very immersive, always with a maximum of three people in the class. At the end of the day, they all go away with a frame panel where they have done cutting, engraving, painting, staining, leading and cementing in one day. Most of the students I get are people that already have an interest in learning about stained-glass and they got the workshop as a gift.

I have also had two work experiences with people from the local school and some people with learning difficulties who have come and done work experience in my studio as well. It’s really people who are keen enough to get in contact and then I will do what I can to share the skills. I haven’t got an official apprentice yet. I have done stuff in schools before, but to be honest, now I’m just so busy that I tend not to.

Tinker Tailor Stained Glass. © Rachel Mulligan

9. What would you recommend to a young person interested in your profession?

I think there’s a lot of work in houses. People want to improve their environment and have something that’s personal about them. So a lot of my work has been front doors and bathroom window, things that make a house look more homely and interesting.

Being proactive about social media and websites and getting your work out there really helps as well. And also working locally. I found local museums have been really good. They have shared my work and then they have bought my work and commissioned me. So getting involved locally, it sort of spreads out. There are also opportunities in bigger studios where they employ people to do conservation and restoration work, which is much more historic and you have to be much more careful with your work.

Lastly, I would say that stained-glass is a very rewarding and fulfilling job because you are using your hands and your creativity. I think my main strength, personally, is that I can make something that fits in, that brings together all the things that people have said they want in the window. It all looks very natural, it takes time to get to that point. I don’t think I did that at the beginning, but I know I can do it now. So I think that’s the sort of skill you can build on. So, yes, I think the main thing is it’s a lifelong interest. I’m always learning, I’m still improving, and there’s still lots I want to explore with it. It’s very rewarding.

10. Do you think that your profession is threatened and in this case, what are the main threats?

I don’t think it is threatened to any great extent yet, but I think it can be. And this is the sort of thing that once it’s gone, it won’t come back. The people that I’m learning from and my source of inspiration are now in their 80s, quite a few of them, and they’re very happy to share the knowledge. I have just written an article about Alfred Fisher, a stained glass professional who

Rachel Mulligan in het studio. © Rachel Mulligan

did windows at Westminster Abbey and Buckingham Palace. He’s really at the top of his profession and he’s very generous with his knowledge. I spent a couple of days with him this last year, and I’m writing an article about his training at Whitefriars. I’ve written up his knowledge and everything that I want to keep and share.

So learning can be a difficulty. There are a lot of people with an interest in stained glass and there are lots of classes to learn. But the way to get the higher level skills is to deal with it and to understand that you not just designing a front door for a house or a window for a church. Your creation will be part of the built heritage. The skills to do that kind of work and the understanding of how it’s going to work in different lights, how much paint to put on, that takes longer to learn. I found I’ve learned a lot by doing it and looking at windows, talking to people, sort of building little bits of knowledge and adding to it. But it’s only when you’ve actually done it and you stood back and looked at it and you think, oh, that bit could have been different.

Another difficulty is getting the materials you need. The place in London where I used to go for materials shut. They moved to Liverpool. There’s another place in Reading where I can get to in about an hour and pick out the things I want, but they don’t keep the glass I want. For the glass, I have to go to Germany or France. Before Brexit, I used to drive, fill the boot and drive back. I have also had it shipped over, which is more expensive. For the paints, we have a group of five or six people from Surrey, some of them old students who set up their studios, and some other people that we have met. So we try to share the order, and that brings down the cost of travel. So one solution, I suppose, would be for more people to get together and order in bulk.

11. Which could be the solutions to better support your profession and preserve the transmission of skills?

I think mentoring is absolutely essential. I have had unofficial mentors in the stained glass profession who have helped me and to whom I know I can go and ask something. So I think building community is good. That will help us thrive.

Some museums do workshops and exhibitions that attract people. The Ely Museum, for example, is an amazing place. I think having places like this helps to promote stained glass and artists who work with it. We had a tearing exhibition of master glass painters’ work that went to ten different locations around the UK. A lot of them were cathedrals because they got the space to show them.

Lastly, I think that having stained glass on the Red List of Endangered Crafts will help us with a huge campaign to save it. There are definite difficulties, and it’s crept up and it’s still creeping up, and that’s a danger. But if it keeps going the way it has been, the elders will go, the studios are shutting and other studios will shut. But there’s hope.

You can find out more about Rachel Mulligan´s work and portfolio on her website as well as on Instagram, Facebook and Twitter.

Mad’in Europe (MIE) is a small company committed to promoting craft professionals and crafts professions and to supporting the transmission of crafts skills at a European level. Its multilingual portal gathers a large audience around the profiles of 1,500 crafts, restorers and fine crafts professionals. As a member of some European organizations and thanks to its wide European network MIE participates in several transversal activities including Erasmus and Horizon projects which focus on valorisation of crafts, preservation of traditional know-how, and raising awareness among young people, for whom the sector represents a source of employment.

Mad’in Europe (MIE) is a small company committed to promoting craft professionals and crafts professions and to supporting the transmission of crafts skills at a European level. Its multilingual portal gathers a large audience around the profiles of 1,500 crafts, restorers and fine crafts professionals. As a member of some European organizations and thanks to its wide European network MIE participates in several transversal activities including Erasmus and Horizon projects which focus on valorisation of crafts, preservation of traditional know-how, and raising awareness among young people, for whom the sector represents a source of employment.

Future for Religious Heritage (FRH) is an independent, non-faith, non-profit European network founded in 2011 and based in Brussels to promote, encourage and support the safeguard, maintenance, conservation, restoration, accessibility and embellishment of historic places of worship. Our network represents more than 80 organisations and over 120 professionals from 36 countries, which includes NGOs, governmental organisations, religious and university departments, and individuals. We are one of the 36 European networks currently supported by the Creative Europe Networks programme.

Future for Religious Heritage (FRH) is an independent, non-faith, non-profit European network founded in 2011 and based in Brussels to promote, encourage and support the safeguard, maintenance, conservation, restoration, accessibility and embellishment of historic places of worship. Our network represents more than 80 organisations and over 120 professionals from 36 countries, which includes NGOs, governmental organisations, religious and university departments, and individuals. We are one of the 36 European networks currently supported by the Creative Europe Networks programme.

Follow us: