by Becky Clark*

The Church of England has forty-two cathedrals: the oldest foundation is the Mother Church – Canterbury Cathedral – founded by Augustine of Canterbury in AD597, whilst the youngest is Guildford, consecrated in 1961. In terms of architectural history they are collectively some of the very best buildings in the country, evidencing over 1400 years of development, ingenuity and work. Although each cathedral is unique not only in historical terms but also in terms of its place within its city and region, there has recently been an increased effort to identify those traits and characteristics which allow them to be appreciated as a group. Key to this has been an understanding of how their extraordinary shared history is playing a fundamental part in economic and social regeneration and sustainability across the country.

Worcester Cathedral is still at the heart of its city. © The Archbishops’ Council/Paul Barker

Some of England’s cathedrals have always been famous, busy and monetised. For example, the cults of Thomas Becket at Canterbury or St Cuthbert at Durham have attracted pilgrims, gawpers, petitioners and tourists for hundreds of years. Whole industries of guest houses, eating places, and sellers of dubious religious relics grew up around significant sites. Some of them are still very much in evidence. So in some ways an exploration of the economic and social contribution of cathedrals is not going to bring up anything new. However what is new is an appreciation of the place cathedrals have in what are today seen as secular concerns, such as regeneration, community building and local economic growth.

In 2014 the Association of English Cathedrals commissioned a report looking at the contribution made by cathedrals nationally. This included several case studies which focused on different ‘types’ of cathedrals. Due to the unique way in which each cathedral has developed and is run, a strict system of catergorisation is neither possible nor helpful, but for the purposes of identifying shared characteristics, opportunities and issues, the forty-two were grouped as follows:

• Large international (e.g. Canterbury, Durham)

• Medium, historic (e.g. Chester, Exeter)

• Medium, modern (Guildford and Truro)

• Parish church (e.g. Blackburn, Derby)

• Urban (e.g. Birmingham, Liverpool)

Their impact was then assessed against a range of criteria which covered both the direct and indirect economic effects. Direct effects were those concerning employment and expenditure linked to the cathedral itself, whilst indirect included visitor activity and expenditure in the wider area. To this data was added information on the level of social impact, classed under four categories: worship, education, volunteering, and community outreach. Additionally an in-depth case study was completed on at least one cathedral out of each of the groupings.

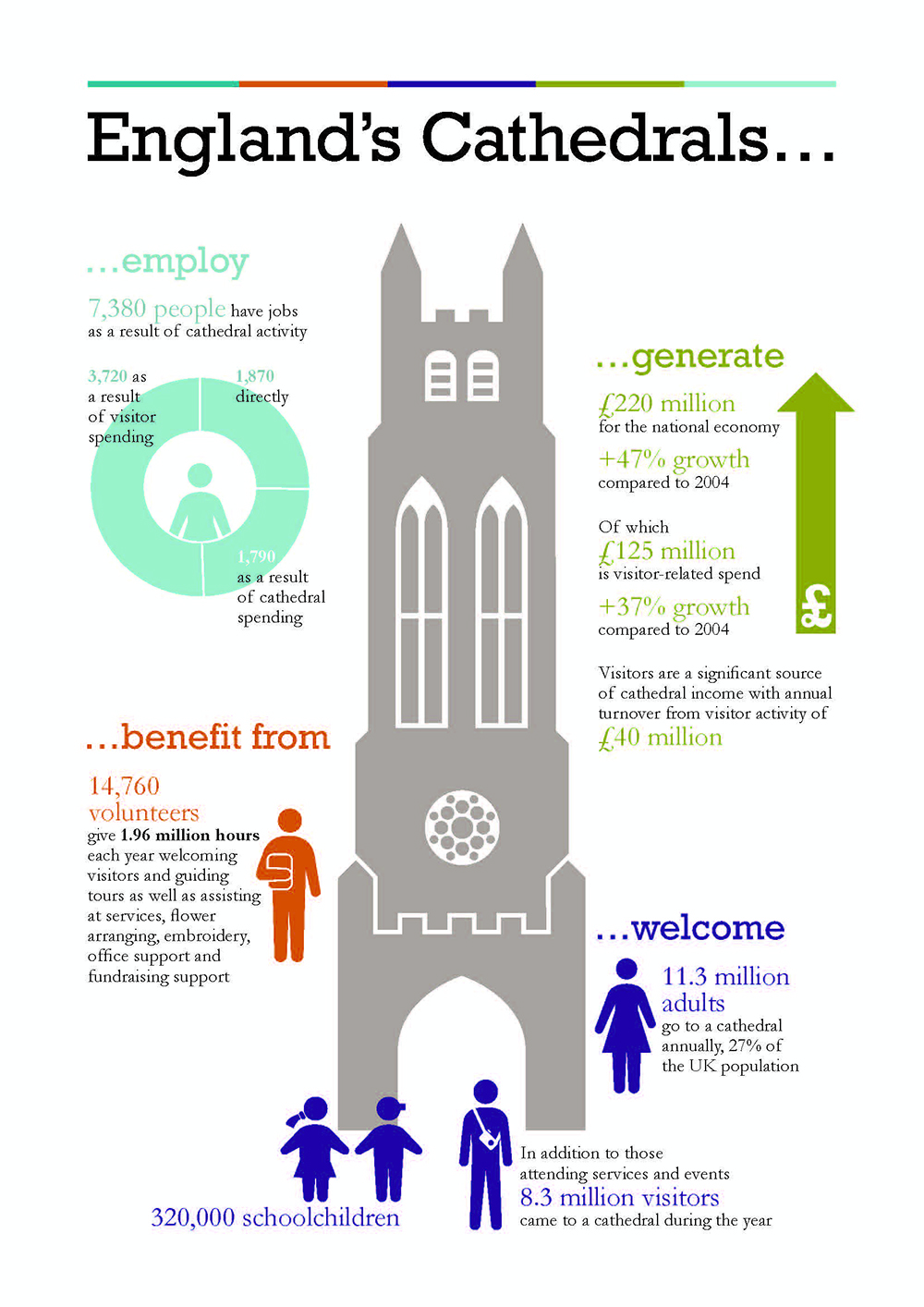

Demonstrating growth – the headline findings of a recent survey. © The Association of English Cathedrals

The results were compared to a similar report completed in 2004, mapping ten years of change. And they were astounding. Figure 2 shows the results in an infographic. The top line findings were:

• In 2013, 8.3 million people visited cathedrals as tourists and visitors. This is in addition to the millions who attend services, and the hundreds of thousands of schoolchildren who visited as part of educational programmes. Adding in these takes the total number to well over 11 million visitors annually, equal to all visitors to English Heritage’s 420+ sites.

• Cathedrals contribute £220 million annually to the national economy, a rise of 47% from ten years ago.

• £125 million of this comes directly from visitor-related spend, up 37% from 2004, showing that not only are cathedrals growing, they are growing by encouraging visitors and tourism.

• Across England 7,380 people are employed thanks to cathedrals

• 14,760 people volunteer at cathedrals, in roles ranging from flower arranging and embroidery through to tour guiding and office support.

Add to this the Church of England’s 2013 Church Growth Research Project (www.churchgrowthresearch.org.uk/), which showed a 37% increase in cathedrals’ worshipping congregations over the past 10 years, and you have one of the largest, most successful, and most visible parts of the Church of England, spread all across the country, a truly nationwide resource.

Undoubtedly the national picture was telling us that cathedrals were a powerful force for economic and social growth. But what also became apparent, through both the report and through the work being done by individual cathedrals, was that cathedrals saw themselves as not just part of their localities, but leaders of regeneration within it. Not all English cathedrals are large and grand. Some – mostly those in the ‘parish church’ and ‘urban’ categories used by the researchers – used to be parish churches, aggrandised in the 19th and early 20th centuries to fit the spiritual demands of growing populations. Many of these are in cities which have seen a subsequent decline in manufacturing and industry, and the concentration of economic growth in the south-east of England, leaving some communities struggling. For these places tourism is not (or at least not yet) a major force. What is needed is local civic regeneration. Urban and parish church cathedrals are proving that they want to be at the heart of this.

There are several projects which could serve as exemplars, but one which is happening right now is focusing on Blackburn Cathedral (Figure 3). Blackburn, in Lancashire, north-west England, is not a major tourist destination, but the cathedral does attract significant numbers of visitors, estimated at 18,700 in 2013.

Blackburn is currently engaged in a major redevelopment project as part of the Cathedral Quarter scheme to upgrade a large site in the town centre. The project is due for completion in autumn 2015 and includes a new hotel, office blocks, public realm improvements and transport interchange, involving numerous public agencies and private sector partners. Cathedral staff have played a key role since 2000, driving, planning and delivering this project, with a subsidiary company, Blackburn Cathedral Development Company, managing the Cathedral Court element of the project with the support of professional design and project management contractors.

Blackburn Cathedral is growing to meet the needs of its community. © Angelo Hornack, reproduced by permission of Blackburn Cathedral

The Cathedral Court will include a library, refectory, conference room, hospitality suite, offices, underground car park and accommodation. It will also include a new cloister and garth – the first cloister built at an English cathedral since the reformation. A total of £6.8 million will be invested in the cathedral, with the majority of funding coming from the Homes and Communities Agency and the Borough Council (a large part of whose contribution is from the European Regional Development Fund). The remainder has been raised by the cathedral through the sale of leases on previously undeveloped land, contributions from the Cathedral Trust, and extensive fundraising efforts, which are still on-going.

The project represents a major improvement to the urban environment and is expected to increase the number of people visiting the cathedral by improving both visibility and accessibility. It will directly increase the numbers of people living in Blackburn town centre as a result of the new accommodation being built. The project will also increase the cathedral’s capacity to host musical, education and community activities, further developing community outreach work.

In line with its policy of using local suppliers wherever possible, the cathedral decided at an early stage to use a local building firm to carry out the work, a move which benefited the local economy by an estimated £7.8 million.

When complete, it is hoped that the Cathedral Court project will bring a range of financial benefits. For example, the cathedral will save an estimated £33,000 per year on accommodation (as its own clergy and music scholars will live in some of the new housing it is building), earn an additional £10,500 from the rental of office space, and between £15,000 to £20,000 by licensing or franchising refectory services. Overall, it is estimated that cathedral income will increase from the current £15,000 to around £25,000 per year as a result. These are all sustainable, long-term gains.

It is also anticipated that the project will boost revenue by increasing the cathedral’s attractiveness as a venue for events. The cathedral already hosts a range of civic ceremonies, musical performances, art exhibitions and events, and recently commissioned an events management consultancy to conduct a feasibility study on using the cathedral for corporate events and meetings, to better understand the revenue this could generate and the type of events that would be appropriate. The study concluded that there was already significant demand amongst businesses thanks to the cathedral’s scale and architecture.

The scale of the Blackburn model cannot be re-created everywhere, but elements of it are applicable to many religious buildings. The key finding has been that where regeneration efforts are needed, cathedrals (often situated in the historic centre of their town or city) are central to success.

In Peterborough the resurrection of the central town square has been done in conjunction with works to provide open, level access to the beautiful medieval cathedral.

In Wakefield (Figure 4) the controversial removal of the Victorian pews and stone floor, and replacement with a modern floor, underfloor heating and moveable chairs, has doubled the visitor numbers, with almost all visitors coming from the immediate area to enjoy the rejuvenation of ‘their’ cathedral. The cathedral has been able to open its doors to a new range of events and groups, making it a real focus for communities coming together.

Wakefield’s new floor and more flexible space has seen local people flooding in to enjoy it in many different ways. © Wakefield Cathedral/Harriet Evans

In Leicester (Figure 5), efforts to create a cathedral quarter with a green space available to all in the city were well underway even before the discovery of the remains of King Richard III and the re-burial in the cathedral. These were linked directly into the Council’s strategy to build up civic amenities in the city. More often than not the outside space cathedrals have is key to the part they play in civic regeneration. In improving this and linking it to secular areas of their cities, cathedrals also improve ease of access to the church itself. These models could be applied, at differing scales, to cathedrals, major churches and many other places of worship anywhere in Europe.

Leicester Cathedral was expanding its civic role even before the discovery of King Richard III’s bones. © The Dean and Chapter of Leicester Cathedral

By creatively engaging with and leading civic regeneration, England’s cathedrals are ensuring that they remain relevant and central to their communities. As agents of regeneration and economic growth, cathedrals give but also gain, in all the ways that matter to them – community building, income generation, and most importantly, their Christian mission. This path is not easy – it costs money and takes up staff and clergy time, it often leads to changes and disruption which have to be justified to loyal congregations. And there is no guarantee it will work, meaning it requires an appetite for risk which is often lacking in religious communities. However there is growing evidence and experience which demonstrates that this approach works, increasing the impact of cathedrals in all aspects of local and national life. In continuing to serve the people they are there to serve, cathedrals need to look not just to the past, but to the future.

* Becky Clark is the Church of England’s Senior Cathedrals Officer, and runs the Cathedrals Fabric Commission for England. In this role she has responsibility and oversight for all buildings-related matters for England’s 42 Anglican cathedrals. The role involves travel all over England (and occasionally further afield) and covers everything from archaeology and architecture to new builds and solar panels. Previously Becky worked for English Heritage (now Historic England) on the Heritage Protection Reform and then running the Chief Executive’s office. She has also worked for the National Trust and Thinktank, Birmingham’s science museum. Becky studied Classical Archaeology and Ancient History at Oxford and has a passion for the classical world.

Picture by Edward Moss Photography www.edwardmoss.co.uk

All rights reserved.

Rebecca Clarke

Becky Clark

For more information on the care and management of the Church of England’s 42 cathedrals and 16,000 parish churches, visit www.churchcare.co.uk

The research report can be read in full and for free on the Association of English Cathedrals website, under ‘Resources’.

You can follow progress at Blackburn Cathedral and find out how to support their fundraising appeal via Twitter: @bbcathedral

To find out more about the 42 cathedrals, check out the new book, Director’s Choice: Cathedrals of the Church of England by Janet Gough, available from online bookshops.

Follow us: