Between the 11th century and the first half of the 19th century, more than 500 monastic buildings belonging to the most diverse orders and religious congregations were founded in Portugal. Over the several centuries of their existence, these buildings suffered various damage, but it was the abolition of the religious orders, which occurred in the context of the implementation of liberalism, which caused them the greatest number of transformations as a result of the loss of their traditional use as religious space.

In Portugal, the process of extinction of the religious orders began in the early 1820s through the closure of monastic buildings with fewer than twelve religious; it reached its peak in 1834, with the publication of the decree that determined the closure of all the male religious houses existing on the Portuguese territory; and it lasted until the beginning of the 20th century, through the gradual closure of the female houses, which were closed after the death of the last nun.

After the extinction of the religious houses, all their movable and immovable assets became the state’s property. The former, consisting of the most varied goods of daily use, works of art, libraries, religious objects, and objects of gold, silver and jewellery, had different destinations, while the latter, consisting of the monastic buildings and precincts where the religious communities lived, were assigned to public service or sold to private individuals.

At this time, the enormous potential of these properties as highly versatile spaces became evident, both in terms of their size and architectural and artistic quality, and in terms of their privileged locations. Thus, the monastic buildings and their grounds were correspondingly given over to the most diverse public and private usages, whether hospitals, courts, prisons, government offices, military barracks, schools, theatres, household residences and factories, while some remained abandoned. In the meantime, others were ultimately partial or totally demolished in order to make way for new buildings, or to improve traffic circulation and to enable the renovation and growth of urban areas.

Nevertheless, and in parallel with the awakening of heritage awareness in Portugal, in 1910 a small part of these buildings was included on the first heritage list in Portugal and received conservation interventions. These included the Monastery of Jerónimos, the Convent of Christ in Tomar, the Monastery of Batalha, the Monastery of Alcobaça and the Monastery-Basilica-Palace of Mafra (fig. 1), which are now included in the World Heritage list.

Fig. 1 – Monastery of Batalha, Batalha; Monastery of Alcobaça, Alcobaça; Convent-Basilic-Palace of Mafra, Mafra (photo: author, 2018).

However, it was from the 1980s onwards, in the context of the sharp increase in the number of listed properties, that the great majority of monastic buildings were recognised as cultural heritage and reused for other purposes that guarantee the preservation of their cultural values.

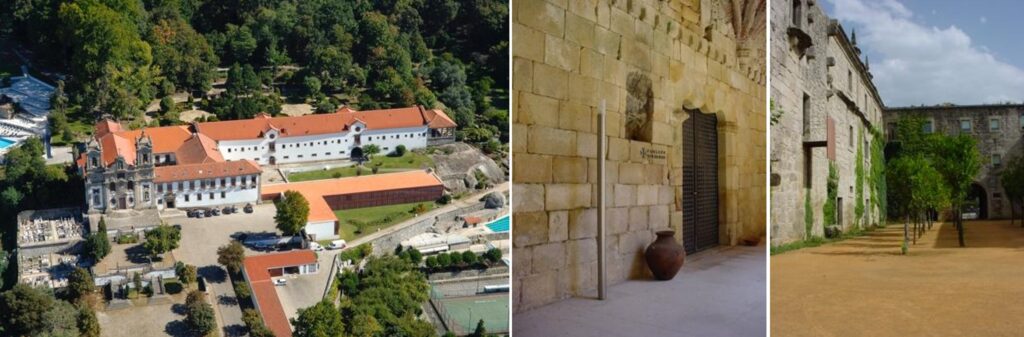

Some of them were included in the “Pousadas Program” – a state intervention program for the reuse of built heritage for tourism purposes which began in the 1960s – representing more than 60% of the total buildings included in this program, where some of them, such as the Monastery of Santa Marinha da Costa, the Convent of Flor da Rosa, and the Monastery de Santa Maria do Bouro (fig. 2), were considered paradigmatic examples of the recent history of heritage restoration in Portugal.

Fig. 2 – Monastery of Santa Marinha da Costa, Guimarães (photo: CMG, Paulo Pacheco, 2007); Monastery of Santa Maria do Bouro, Braga (photo: author, 2001); Convent of Flor da Rosa, Crato (photo: author, 2001).

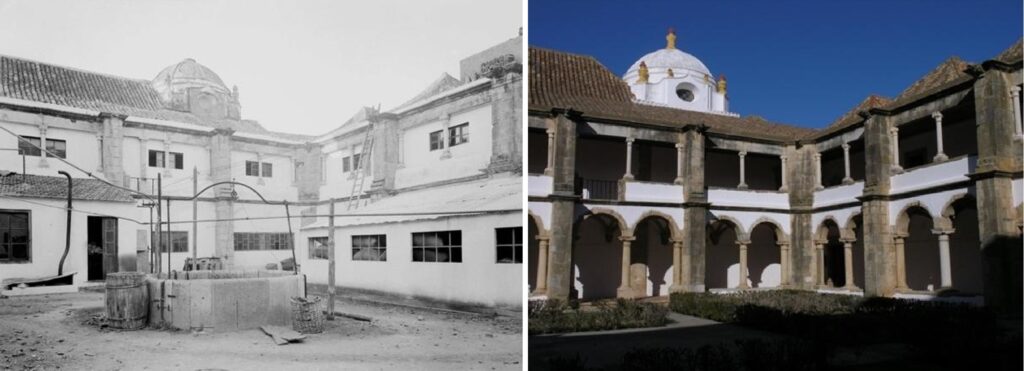

At a more local scale, some of these buildings were attributed to cultural functions, as for example, the Convent of Nossa Senhora da Assunção in Faro (Fig. 4). This Poor Clares Convent was transformed into a cork factory after the secularisation and has functioned as a museum since the 1970s (Municipal Museum of Faro).

Fig. 3 – Convent of Nossa Senhora da Assunção, Faro (photos: SIPA-DGPC, 1947; author, 2005).

Other monastic buildings received mixed-use programs. One of them, was the Monastery of Tibães (Fig. 5). This monastery was sold to private owners after the secularization in 1834, with the church remaining with its religious use, and in the 1970s the building was abandoned and disused. In 1986, the Portuguese State bought the building, started conservation and restoration works and implemented an adaptive reuse program that sought the coexistence between the “old” and the new uses, and that included the whole monastic complex (church, monastic dependencies and monastic enclosure). The church was kept for worship, while the former monastic dependencies received a monastic community (with the responsibility of managing an inn and a restaurant), a museum (with museum spaces, a centre for the study of monastic orders, and historical gardens), and also, conservation and restoration laboratories. Finally, the former monastic enclosure was also opened to public use, playing a central role in the dissemination and interpretation activities developed in the monastic building.

Fig. 4 – Monastery of Tibães, Braga (photo: DRCN, 2018).

Despite all these interventions, today, almost two centuries on from the dissolution of the religious houses, some of these buildings still remain abandoned and disused, while others are cyclically losing their post-monastic usages. One recent example is the decision to close several hospitals in Colina de Santana (an area in the centre of Lisbon) that were former convents – São José, Miguel Bombarda, Capuchos, Santa Marta, and Desterro (Fig. 6) – which served as public hospitals following the secularization. But similar situations have already taken place in the past as, for example, following the reformulation of the military services (with the overwhelming majority installed in former religious houses) or with the “natural dissolution” of the few monastic communities that returned to their buildings after the secularization, such as the recent example of the Monastery of Cartuxa in Évora, that lost its religious community in 2019.

Fig. 5 – Convent of Nossa Senhora do Desterro, Lisbon (photo: AML, José Vicente, 2014).

Fig. 6 – Monastery of Cartuxa, Évora (photo: author, 1997).

This last case – the Monastery of Cartuxa – represents an excellent example of continuity of the religious use, since, although it was secularized in 1834 and functioned with different uses, the Carthusian monks returned to the monastery in 1960, where they lived for nearly 60 years, being then replaced by a nuns’ community that recently settled in the building. But this is a unique case, since the very large majority of the monastic buildings are being reused for non-religious functions. These, however, preserve the buildings’ cultural values and guarantee their protection for future generations while also having cultural, social, environmental, and economically sustainable benefits and contributing to more cohesive and inclusive societies.

By Catarina Almeida Marado (PhD), Centre for Social Studies, University of Coimbra, Portugal.

catarinamarado@ces.uc.pt | https://ces.uc.pt/en/ces/pessoas/investigadoras-es/catarina-almeida-marado

Follow us: